Most likely because of SOM’s image as a monolithic institution with few starchitects or inter-office distinctions at the time, Marine Midland Center is inaccurately credited to Bunshaft by multiple online sources and even a prominent book about the city’s history in which the author snarkily describes the design as the architect’s “revenge on his hometown” for not getting his SUNY Buffalo megastructure built. Alas, whatever reasons behind the bank’s decision to not work with Bunshaft on this remain unknown. “I’m not really sure how it came to the San Francisco office. But somehow it came to me,” Goldstein recalled in a 2008 interview with the Art Institute of Chicago. He died in 2015. Nicholas Adams, author of both a Bunshaft biography and a history of SOM, is also unsure. “I asked Mark Goldstein this before he died and he didn’t have a good answer. ‘Well, they liked our work.’ I just don’t know. No one knows,” the historian told me in 2019. “It was interesting that Mark didn’t answer the question, I pressed him a couple of times,” he added. “Seymour may have liked SOM and decided he didn’t want to work with Bunshaft or vice versa because the project didn’t interest him.” In 1972, the same year workers started to move into their new desks inside Marine Midland Center, Bunshaft told the New York Times, “I don’t consider office buildings major architecture anymore.” In 1974, however, two prominent Midtown towers designed by Bunshaft, the Solow and W.R. Grace buildings were completed. His last major project, the National Commercial Bank tower in Jeddah, opened in 1983. The architect and his wife donated works to the Albright-Knox throughout the ‘70s and when Bunshaft won the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1988, Knox II sent Bunshaft a warm letter congratulating him (as did his son, Seymour Knox III). The two men died one month apart in 1990.

Goldstein, meanwhile, loved the commission and the client. He said in his Art Institute of Chicago interview that he considered Knox to be one of his favorite clients ever. “[He] used to take me down to New York on his art-buying sprees, and I would walk into a gallery with him, and it would be like walking in with King Midas—people treated him like royalty. He was such a sweet, wonderful man,” recalled the architect. Later on in the same interview he considered the project “... a very, very thorough job. Not only the shell of the building, but the interiors as well. So that was really a pleasure. And they [Marine Midland] were just wonderful people to work with.” Goldstein recalled in the same interview designing one other Buffalo project, an owner’s suite inside the WPA-era Memorial Auditorium for the NHL’s Buffalo Sabres. The franchise was founded in 1970 by Knox’s sons, Seymour III and Northrup. Like Bunshaft’s banking hall renovation, records of this project have yet to be discovered in SOM’s archives.

Marine Midland Center was included in SOM’s 1963-1973 monograph along with the more famous Marine Midland building in Manhattan, the Hancock Center in Chicago, and one of the San Francisco office’s most celebrated 20th century projects, the Bank of America Center (now known as 555 California Street). In the monograph introduction, former MoMA director Arthur Drexler succinctly summarizes the state of the firm’s reputation at the time, “Once praised for the consistent quality and character of its work, then sometimes criticized for being too consistent, SOM’s recent practice often draws simultaneous praise and blame—to the same building—for the consistent quality of its innovations.” This summary fits the Marine Midland Center quite well. Developers, tenants, and engineers are most likely to praise it for construction quality, floor plate size, user circulation, and energy efficiencies. Fans of modernism appreciate its interior design, art programming, and a forceful-yet-restrained presence on the skyline. Detractors will point out various urban design shortcomings, interpret the interiors as impersonally corporate, and argue that its presence is unacceptably cold and arrogant in a 19th century city traumatized by thoughtless 20th century interventions.

Corporate modernism, for better or worse

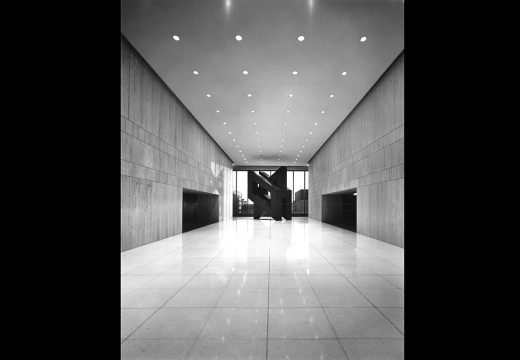

Marine Midland Center occupies two blocks, with Main Street splitting straight down its east and west plazas. A 38-story tower hovers over Main while an L-shaped ancillary building supports the south end of the site and wraps north on the west side. The annex connects to the tower through a bridge that leads to the tower’s third floor lobby which contains an auditorium and cafeteria, sculptures, and impressive city views courtesy floor-to-ceiling windows about twice the height of any other tower floor. The annex building originally contained space for a restaurant and shops on the west section and a branch bank in the south wing. Upon completion, the entire project contained 1.4 million square feet of space including underground parking and a basement area for the bank’s computer center and mechanicals. The facades are clad in 4-inch-thick chamfered precast concrete panels, and finished with washed silicate gravel. The window ribbons have bronze tinted glass panes with dark anodized aluminum frames. An unrealized phase two would have spread east—where Sahlen Field and a parking garage connected to the tower stand today—containing another L-shaped building supporting two smaller towers for hotel, office, and retail space extending the project footprint an additional two blocks east.

Few Buffalonians include it on their personal list of favorite tall buildings, their strongest case against it being its urban design. There was simply too much open space at Marine Midland Center, located at an already quiet and windy southern edge of the CBD. To city leaders at the time, this type of modern urban plaza was in fact a major upgrade over the decaying building stock which mostly traced back to the early 1900s and considered “Buffalo’s skid row” by the time of Marine Midland Center’s construction—years since the former terminus of the Erie Canal had any commercial value. Stretches of the canal were filled in and most of the buildings surrounding them were demolished by the 1960s. SOM presented its first designs to the city in 1968. Private, federal, and state funds to finance its development soon followed. At its groundbreaking ceremony in 1969, Erie County Executive B. John Tustuska called the project a "major transplant" for a "rundown, disheveled, unkempt, and neglected area." Struggling urban cores all over the U.S., especially the industrial northeast, embraced modernism’s towers and plazas around this time as ambitious solutions to urban blight, satisfying the business community and signifying progress to the public.

Marine Midland’s plaza led to intimidating and confusing entrances into the complex, seemingly designed to invite only those who have business to conduct while dissuading spontaneous and casual exploration. If one bravely decided to enter the tower without an invitation, however, they could only hope that the escalators on the both sides of the tower would lead them somewhere welcoming. For those curious and courageous enough, there was indeed a payoff. The third floor of the tower was the social hub of Marine Midland Center, where visitors and workers converged. While more transparent, the annex’s south wing entry is a significant distance from the sidewalk thanks to the severely sloped site. SOM’s solution for this slope was a perfectly flat plaza that created a blank concrete wall along Washington Street which got taller as one walked down to the waterfront, and interrupted only by an entrance to the complex’s underground parking garage. This treatment was repeated on the west side of the complex, where the annex reaches closer to Seneca Street—the cross street along the north side of the complex. Modernist landscaping resulted in large concrete boxes with flowers and honey locust trees that also functioned as places for workers to eat a bag lunch or take a smoke break, but not much else.

The street level of Marine Midland Center’s south end was designed for services and deliveries, effectively surrendering to the site’s hostility established by highway overpasses which run parallel to it and separate downtown from the waterfront. Staircases on both sides of the south end lead to the rear of the annex and a narrower section of the plaza. SOM’s work here spares the CBD of the blight of the highway by spreading itself across Main Street but it created its own intimidating presence. Along the street and under the tower, blank walls, brutal winds, and confusing secondary entry points made for an isolating pedestrian experience. A decade into the building’s life, cars were banned along Main Street for a modest light rail system, furthering the sense of isolation along this end of downtown. The transit project did lead to what were essentially extra-long station shelters (interrupted at Seneca Street) to help pedestrians manage the intense winds between train stop and tower entrance.

A persistent security presence along the outdoor sections of the complex during the bank’s later years assured limited loitering, as if the typically empty plaza’s purpose was to be a concrete moat between the bank and the public instead of a gift to a downtown desperate for attractions. On an overcast weekend afternoon towards the end of the bank’s occupancy, this writer was asked by security to stop photographing the plaza’s enormous Ronald Bladen sculpture. I would have to move to the city-owned sidewalk if I insisted on getting a picture without any trouble.

A sculpture for the skyline

At 60 feet tall, “Vroom, Shhhh” (sometimes spelled “Vroom SH-SH-SH”) , was Bladen’s largest ever and one of the largest modern sculptures in U.S., topping by 10 feet the Picasso sculpture in Chicago’s Civic Center Plaza (1967) commissioned by SOM Chicago’s William Hartmann. Knox personally commissioned the work and would have been quite familiar with the artist’s reputation as a respected minimalist sculptor who had painted in an abstract expressionist style. Unsurprisingly, there’s a chance Knox discovered Bladen through Martha Jackson. His piece, “White and Black Collage” was included in her gallery’s June 1960 exhibit, New Media: New Forms in painting and sculpture while another one of his collages, “Black/Blue/Yellow” (1960), was gifted to the Albright-Knox from Jackson’s collection after her death. If it wasn’t Jackson, it may have indirectly been Nelson Rockefeller, who made Knox the first chairman of the New York State Council on the Arts and placed him on the Empire State Plaza art collection commission. The massive government center in Albany was Rockefeller’s pet project among an impressive list of infrastructure initiatives he shepherded across the state during his reign as governor from 1953 to 1972. Bladen was selected in 1970 to create a sculpture for the Albany project (this was one of the few pieces selected by artists instead of the committee, but Knox would have certainly been aware of the decision). Titled “Cathedral Evening,” Bladen’s steel addition functions as a counteraction to the emptiness of the plaza with its directional lines providing focal guidance to its viewers. In some ways, it resembles a sharply bent version of what he’d come up with in Buffalo.

For Marine Midland Center, Bladen created a steel structure with an open core and painted semigloss black. It is composed of a base, a cantilevered vertical pier, and an angular beam. In his 2019 book on the artist, Robert Mattison explains that the “the sculpture’s surfaces are either thrown into deep shadow or glimmer with reflected light that picks up the blue tint of the sky,” as a result of the semigloss paint. “Simultaneously,” he adds, “these reflections highlight the volume of the work and lend it a mysterious presence.”