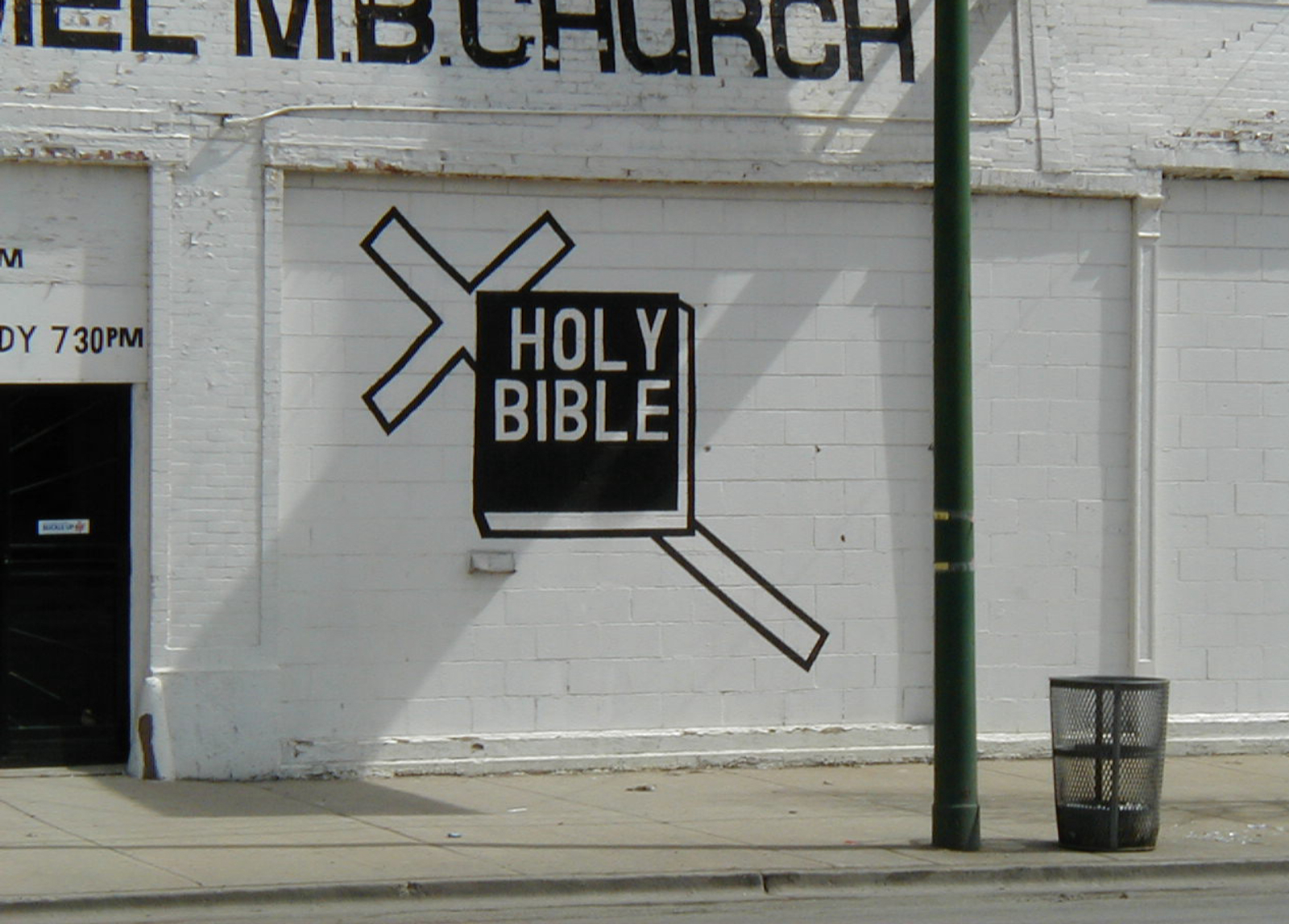

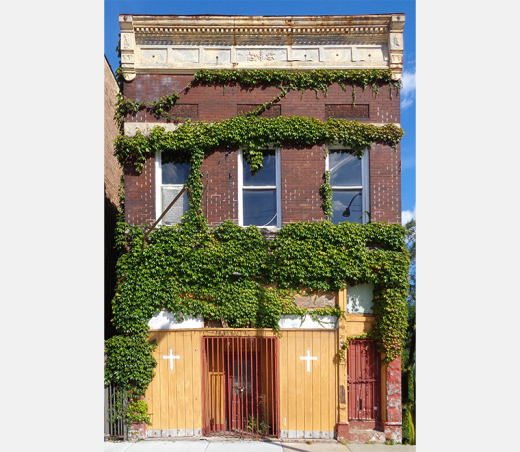

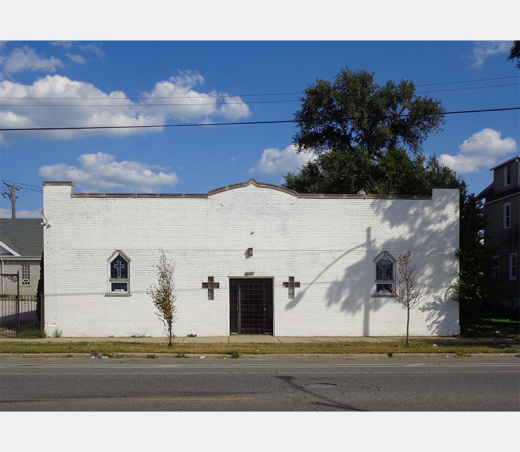

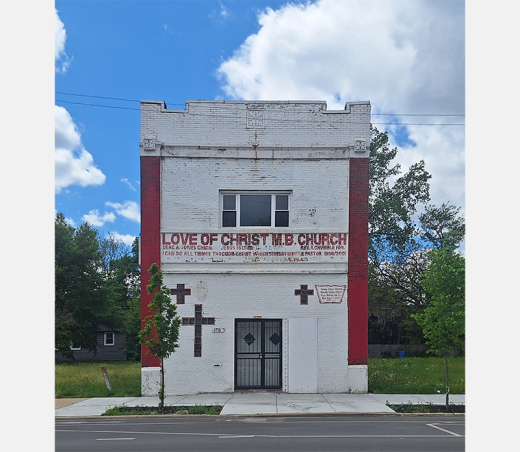

Crosses of Chicago is a series of photographs that documents thirty storefront churches that were located throughout the South and West sides of Chicago between 2005 and 2007. The series captures the bold graphic aesthetic of storefront churches, including hand-painted Latin crosses, signage, and graphic facades, all of which I still find visually compelling. Crosses of Chicago derives from an earlier photographic series entitled Black Type (2001), in which I examined the semiotics of commercial signage in the Black inner-city business districts of Chicago and Baltimore. My interest was also personal. From family members who attended various storefront churches, I have gained greater insight into the often overlooked role and importance of these institutions in their communities.

Graphic facades are a significant part of the culture of poverty. Although they are not entirely absent from middle-class neighborhoods, the cultural geographer Wilbur Zelinsky has demonstrated an emphatically negative correlation between the presence of storefront churches in a given district and measures of socioeconomic well-being.(1) The buildings used as storefront churches are typically unremarkable assemblages of modern construction materials. None of the church buildings that I documented in Crosses of Chicago, for example, had a historic landmark designation. But precisely because the buildings are unremarkable, their users sanctify them graphically. In poor neighborhoods, the custom of painting the facade of the building to distinguish it from its neighbors and embellishing it with symbols or lettering is a universal vernacular expression.

The invitation to contribute to Docomomo US’s special issues on the 2025 annual theme of “Places of Worship,” provided a reason for me to return to the sites that I documented in Crosses of Chicago, now nearly twenty years later. Today, I serve as a Planner for the County of Kane, outside of Chicago, where I have made a concerted effort to spearhead projects that directly improve economically challenged communities. Examples of my planning projects include housing rehabilitation and infrastructure improvements for low- and moderate-income populations. Returning to the storefront churches that I documented on Chicago’s South and West sides solidifies the harsh reality and impact of systemic disinvestment in these communities, as well as the role of these sacred places in helping their members survive systemic disinvestment.