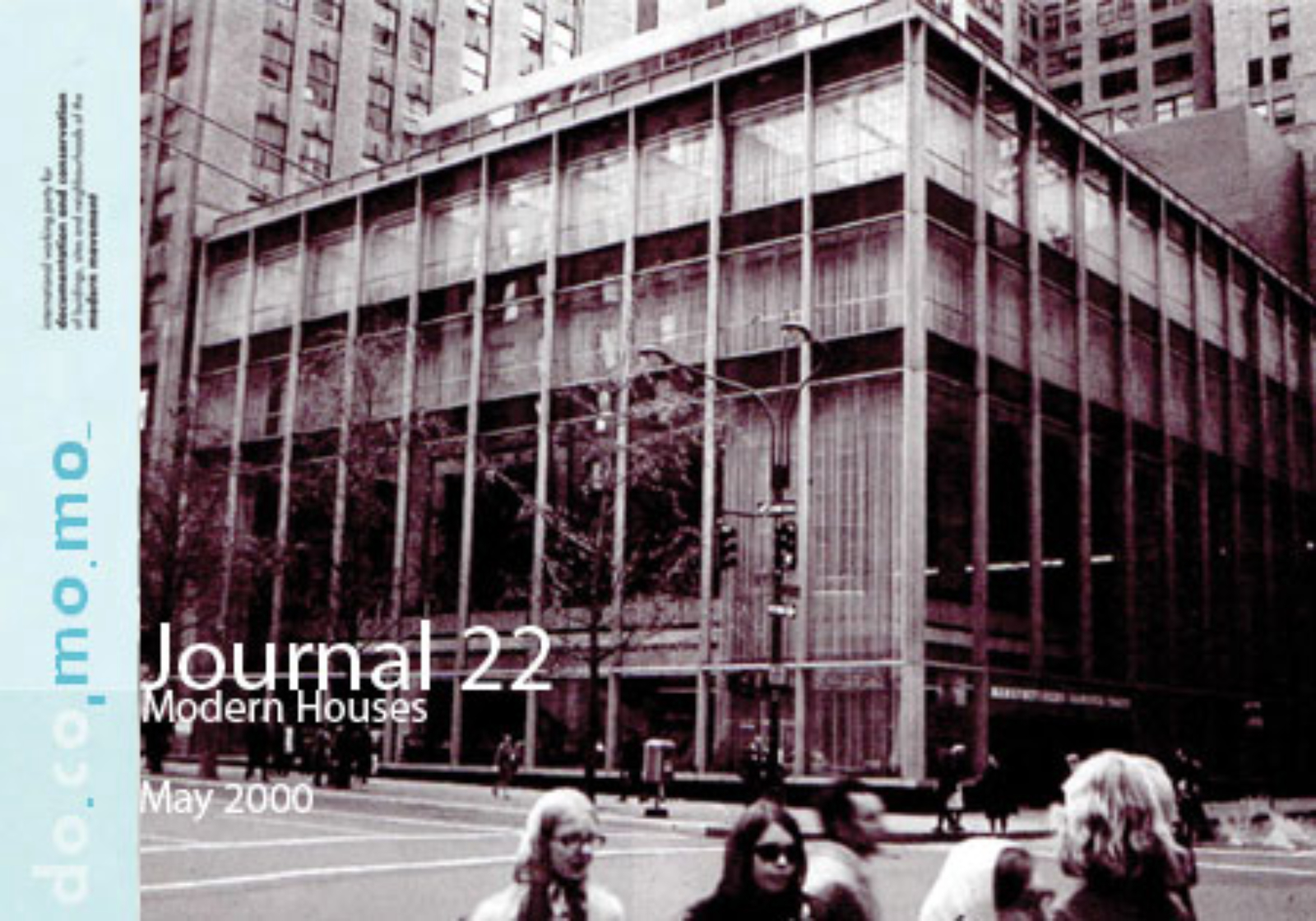

For the third installment of our Flashback series we are highlighting an article on preserving modern corporate interiors written by Docomomo US president, Theodore Prudon titled "Preserving MoMo-interiors in the USA" first published in the Docomomo Journal No. 22 - May 2000: Modern Houses.

For the third installment of our Flashback series we are highlighting an article on preserving modern corporate interiors written by Docomomo US president, Theodore Prudon titled "Preserving MoMo-interiors in the USA" first published in the Docomomo Journal No. 22 - May 2000: Modern Houses.

The Docomomo Journal is published twice a year and is a benefit to Docomomo US International members. To renew or join as an International member, click JOIN.

To be or not to be that is the question.

Aside from the commercial value of the spaces involved, the valuation of the modern interior as architecturally and historically significant as well as the very relationship between the interior and exterior of the buildings are issues that require careful consideration.

by Theo Prudon

Conceptually, as in any style or period, there is little argument as to the need to preserve examples of interiors that best represent the style and intent of the style. However, in dealing with the modern interior some very fundamental questions seem to reoccur every time a preservation battle needs to be waged. Where the significance of the earlier and more traditional interiors was partly derived from an admiration for the craftsmanship of the original creator, as has been discussed by many others, this is not the case with the modernistic spaces. For the modern interior the stylistic and visual integration is more complete and less derived from the individual artifact. The visual relationship between the inside and the outside, i.e. the transparency and the continuation of exterior materials into the interior, is also the result of the dimensional and systemic relationship (i.e. the grid). The last time that this type of visual unity or integration was probably in the gothic era.

An additional issue to be considered is that so much of the interior was achieved with the introduction of modern art, sculpture and furniture. While the integration of art and sculpture has remained, the appreciation of that sculpture may have changed or may have been removed because of its singular value in the art market. Similarly with modern furniture and accessories having appreciated enormously spaces have been stripped and, as a result, their significance is far more difficult to perceive. In this context it is important also to note that some difference exists between preserving residential versus commercial interiors. When a house gets acquired and saved (in spite of real estate pressures) then an appreciation for the value of the interior and its relationship to the overall architecture of the house may exist. For commercial or institutional ownership that significance is nearly always secondary to economic pressures. It is especially those pressures that often lead to demands for change and with as a result, the mutilation or elimination of the interior or interior features that made the interior significant. Several example of this dilemma exist. Where the interior of the TWA Terminal designed by Eero Saarinen is an example of (less than) benign neglect, the Noguchi designed lobby is 666 Fifth Avenue in New York City, hailed by its current owners as preservation, is an example of mutilation. While the TWA Terminal was given landmark status and continues to enjoy some level of protection, the 666 Fifth Avenue Building did not have this cover.

Finally, although the interior is acknowledged to be significant, it may represent only a small portion in an otherwise insignificant building or it may be considered to be hampering the renovation of a structure to a more contemporary (presumably more profitable) use or occupancy. In those instances interiors are threatened usually not just by neglect but by complete removal. A number of these aspects are best illustrated with several current examples.

TWA Terminal, J.F. Kennedy Airport, New York, Eero Saarinen, 1962 interior of this building, as seen in 1970, illustrates the integral relation between the outside and the inside making it impossible to limit preservation and protection to only the exterior. In addition the furnishings, graphic, signage are all part of the overall appearance. Subsequent changes in the airline industry and enormous growth in the number of passengers has created a great deal of pressure on the interior of the building. Photo: Prudon, 1970 |  Kaufmann Conference Center, Institute of International Education, New York City. Building designed by Harrison Abramovitz and Harris, 1964, interior conference center designed by Alvar Aalto. Use of birch plywood and other industrial building materials in a typical Scandinavian manner is clearly visible together with the furniture and fixtures also designed by Aalto. Photo: Prudon 1998. |

Arts Club of Chicago

The interior of the Arts Club of Chicago (designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 1948) was demolished in 1997. Located in a non-descript office building erected directly after World War II this project was one of Mies van der Rohe's first projects in the United States. A small ground floor lobby with an open steel and stone stair leading gave access to the second floor where the galleries were located. The interiors designed for display of artwork, while visible from the outside, were not particularly especially essential to the architecture of this otherwise unassuming building. The architectural character of the interior space, however, was very much that of post-World War II modernism and was an early example of the post war period.

After a protracted battle and an extensive discussion about its merits, the building, the Mies interior included, was demolished to make way for a contemporary real estate venture. Apparently all or parts of the steel and stone stair were installed in the new facility of the club. In the discussion around the building and this interior many of the aspects of the preservation of the modern interior were touched upon. Probably the biggest irony is that this demolition occurred at a time when several blocks away the conference 'Preserving the Recent Past' was taking place.

Exterior/Interior of the Arts Club of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, c. 1948. The Arts Club of Chicago was located in the second floor of an otherwise undistinguished office building. Reached from a street level lobby and a stair to the second floor, the galleries itself were located on the corner of the building and were clearly identifiable. Photo: Prudon 1997. |  Interior of the Arts Club of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, c. 1948. The building that contained the interiors of the Arts Club were demolished and presumably the stair was salvaged and relocated to an another location. In the rear a fragment of the galleries on the second floor is still visible. Building and interiors demolished 1997. Photo Prudon: 1997. |

Kaufmann Conference Center

The Kaufmann Conference Center in New York City, designed by Alvar Aalto in 1972 is a more current example of the same dilemma. The Aalto design was commissioned by Edgar Kaufmann Jr., who had a long involvement with stimulating modern architecture (his father, Edgar Sr., retained Frank Lloyd Wright to build Falling Water and Edgar Jr. taught for many years at Columbia University and was deeply involved at the Museum of Modern Art). The conference center is a series of interiors and rooms off an elevator lobby on the top floor of the building originally designed by Harrison, Abramovitz and Harris as the Institute of International Education in 1962.

The center was dedicated to an educational institution that was aimed at fostering international understanding. Harrison and Abramovitz were the executive architects for the United Nations complex and have been responsible for the design of other significant structures. However, this particular building is not one of the most important examples of their work. Alvar Aalto designed all the spaces, their detail, fixtures and furnishings in the conference center. The materials and colours used are typical for the oeuvre of this Finnish architect. The rooms and their furnishings are all fully intact and is an excellent example of style of architecture not much represented in North America. The design for this center is one of only three projects that were designed and executed by Aalto in the United States.

Kaufmann Conference Center, Institute of International Education, New York City. Building designed by Harrison Abramovitz and Harris, 1964, interior conference center designed by Alvar Aalto. The interior of the conference has remained largely intact and is on excellent example of the later work of Aalto. Photo: Prudon 1998. |

A recent sale of the building and a repositioning of the structure in the current booming real estate market has caused considerable concern about the future of this interior. Where the office spaces on the lower floors have been converted into office condominiums, persistent rumours about the pending 'modernization' exist. Because the building nor its interiors have been designated 'landmarks', no effective protection of exists. (It is important to understand that it is impossible within the American legal construct to designate an interior unless there is a clear presumption of public access, otherwise this would be considered 'taking' without due compensation). In the instance of this building the danger is not the demolition of the building but more the demolition of the space or the gradual mutilation as result of the removal or elimination of significant features. For instance, with the removal of the light fixtures or the furniture or certain wall treatments the space is no longer 'whole' and as result the argument for preservation has been diminished and has become even more difficult. Dismantling and moving such a space to another location is not really a (viable or suitable) alternative. It is likely that, if something were to happen to these spaces and it would be noticed, this will be an important preservation battle and will be a benchmark and test case for the future.

Manufacturer’s Hanover Bank

In the early 1950's Manufacturers Hanover Trust commissioned Skidmore Owings & Merrill to design a new branch bank on a prominent location on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 43rd Street. The design by Gordon Bunshaft was a marked contrast to an earlier design prepared by an other architect, Alfred Easton Poor. That structure was more Moderne than modern in style and was dominated by a solidly looking limestone facade, the exact opposite of the transparent and open facade of the branch bank that got ultimately built. Once completed the building was hailed because of its openness and its break with the view of the branch bank as a fortress. The safe was not concealed but was rather shown off as a sculpture. The very transparency was not just a philosophical statement but was also an important architectural feature. The inside architecture and its appearance towards the outside was very much part of the overall and intended architectural expression.

This transparency was further modulated by the use of drapes. By leaving these partially open or closed some degree of privacy and to use John. Ruskin's word 'veiling' was suggested. The interior and the exterior had become one. The exterior of the building has been designated a New York City landmark. Because of the legal limitations mentioned earlier, the interior was not included in that protection, although an argument could have been made considering that the banking hall was always a public space. However, the net result of not designating the interior is a visual disaster. It is also illustrative of the potential fallacies and difficulties ahead in dealing with similar buildings. The changes made, while all not completely permanent, are visually so poor and disruptive that the whole architectural ensemble has lost the very clarity of the original design. In other words the very reason for its preservation, is being compromised and eliminated by the subsequent changes. For instance, the introduction of new lighting in the ceiling (the original layout of the luminous ceiling has been maintained) has created no doubt a more efficient lighting but a space that looks naked and is very visible because of the elimination of the drapes. Inappropriate Furniture installations are clearly visible and a new enclosed ATM facility looks ill mannered and badly built in this context. From what is visible today it is very difficult to understand seminal role of this building in the development of modern architecture in general and as a visual prototype for branch banks across the country.

Manufacturer's Hanover Trust Company, Branch Bank, Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore Owings, and Merrill (SOM), c. 1950. This branch bank with its completely open appearance was a totally new direction in the banking industry. The interior was on integral part of the exterior of the building and the safe was displayed as a sculpture on the front of the building. The curtains and shades were used originally to create a 'veiling' of the interior. In its present configuration the curtains ore gone, the interior is aggressively lit and inappropriate furniture is stacked against the windows obliterating the transparency of the original design still visible here. Photo: Prudon 1970. |

Lever House

Where the interior of the Manufacturer's Hanover Bank is significant primarily as a complement to the exterior architecture, the interiors of the Lever House are largely unknown. Lever House, New York City, also designed Gordon Bunshaft in the early 1950's, has been the subject of much discussion because of the issues surrounding the repair and replacement of its early curt9in wall. After extensive studies the exterior wall will be replaced in its entirety with new wall of better technical detail but with architecturally the same appearance. While most interest has focused on issues surrounding the preservation of the exterior of this building, much of the interiors have been lost. General office and support spaces had long since been renovated and their original character had been lost in one or another modernization. However, the senior executives spaces were designed by Raymond Loewy, an important American industrial designer and including probably a great deal of his furniture and accessories. Very little of this remains. The building is currently vacant and ready for occupancy by others than the Lever Company. While some years ago many of the original furniture and finishes still existed much of this is gone without much fanfare. This is the more ironic because the battle for the preservation of Lever House as an icon of modern architecture was a major milestone in the recognition and acceptance of the need to preserve modern architecture.

Awareness

The realization that modern interior spaces need to be valued and preserved is slowly growing. However, what is lacking is a comprehensive understanding what this will take and a series of strategies as to how this may be accomplished philosophically and practically. Aside from the practical and legal considerations, the most serious threat remains the meteoric rise in land and real estate values. For residential and commercial architecture the issues are the same. The booming of the real estate industry has made small buildings worthwhile demolishing in order to build bigger and, presumably, more desirable buildings. The value of individual pieces of furniture and accessories has caused stripping of interiors. In some ways the preservation struggle for the modern interior may, at this time, be compared with that of saving an early manuscript. The complete can be read only by a few. The value of the individual pages as decorative features far outstrips the value of the manuscript as an intact and complete whole. It is time to teach more people how to read. The preservation of the interior needs to be an integral part of the preservation of the building as a whole. Without their interiors, many examples of modern architecture become meaningless and possibly not worth preserving.

Lever House, New York City, Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill(SOM), c. 1950. The exterior Lever House was designated a New York City landmark a decade ago. This designation was one of the first recognitions of the landmark quality of modern architecture. An extensive curtain wall rehabilitation and replacement is planned. Photo: Prudon, 1998 |  Lever House, New York City, Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM), c. 1950. While the exterior architecture as designed by Bunshaft is protected, the interiors that were the work of such designers as Raymond Loewy was not. A conference room/dining room shows both the original architectural finishes and the furnishings but no longer existing today. |

Theodore Prudon is a leading expert on the preservation of modern architecture and a practicing architect in New York City. Dr. Prudon has worked on the terra cotta restoration of the Woolworth Building, the exterior restoration of the Chrysler Building, and of a 1941 Lescaze townhouse in Manhattan. Dr. Prudon teaches preservation at Columbia University and Pratt Institute. He is the recipient of a Graham Foundation Individual grant for his book “Preservation of Modern Architecture”. He is the founding President of Docomomo US and a board member of Docomomo International.