By Marlana Moore

By Marlana MooreNew Jersey is a state not often renowned for its beauty, elegance and innovation, especially in context to its postwar suburban development. My internship for Docomomo US New York/Tristate took me through twenty-five years of the periodical Progressive Architecture in search of New Jersey modernism. Progressive Architecture was a national publication active in the heyday of modernism, from the 1940s – 1980s which was meant to showcase innovative buildings, trends, methods and practices occurring in the field of architecture. The internship program I participated in, part of the Rutgers University Department of Art History, seeks to identify and document modernist architecture in New Jersey. The sites I found have been added to a growing database of buildings, sites and architects who were active in New Jersey.

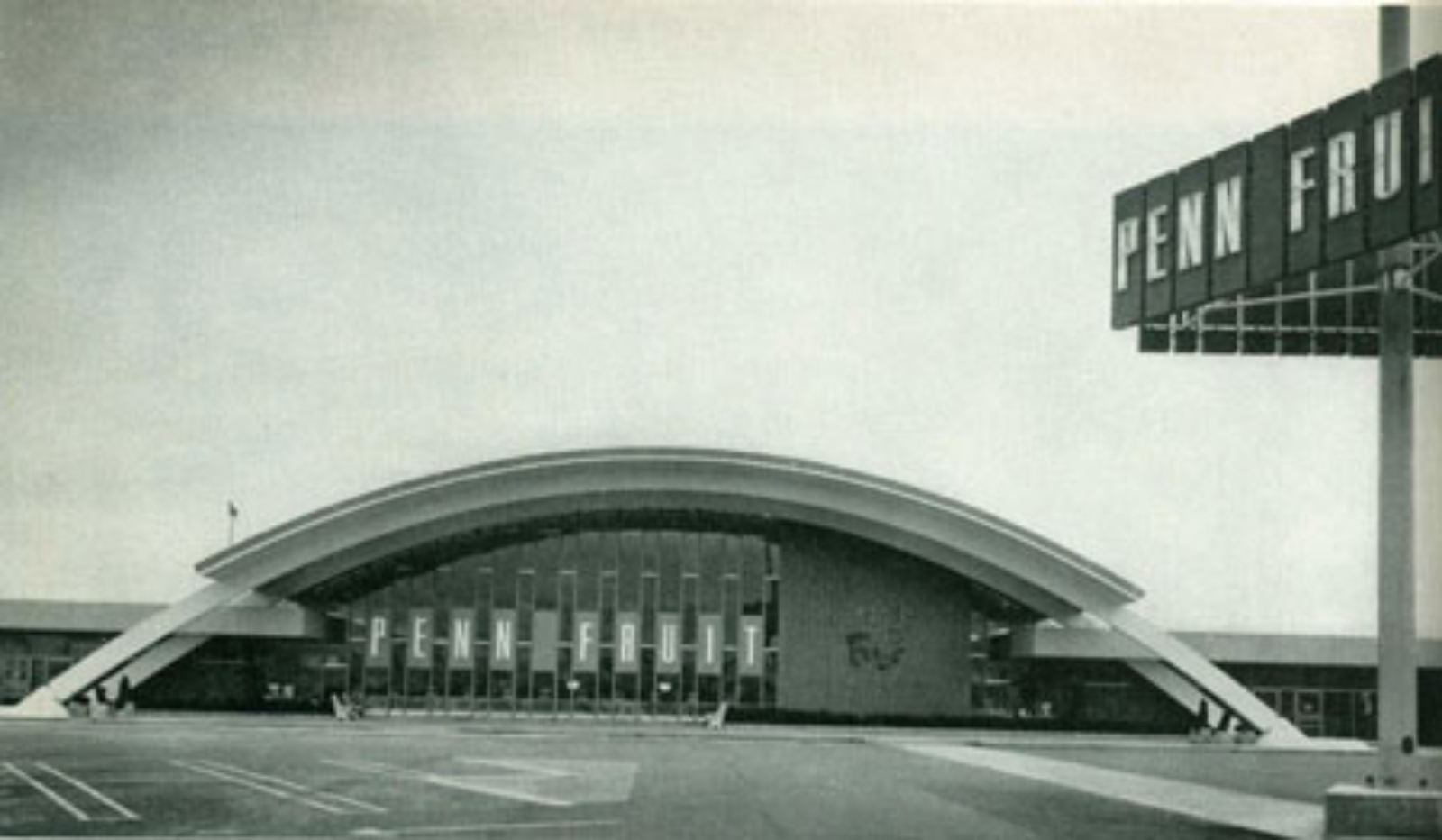

Photo (above): Penn Fruit by Victor Gruen & Associates, located at 100 Black Horse Pike in Audubon, NJ. Photographed by Lawerence S. Williams. Scanned from Progressive Architecture, July 1956, page 100.

My survey found 68 sites (concepts, buildings, or plans) throughout the state that were considered to be at the cutting edge in the time they were built or proposed to be built. There were sites in sixteen of New Jersey's twenty one counties. Sites were most highly concentrated where suburban development took place outside of New York City and Philadelphia. Few sites were found in New Jersey's most rural counties – those in the southern and northwestern parts of the state. A range of architecture firms contributed to the cutting edge architecture featured in my survey, including leading national architects IM Pei, Edward Durrell Stone, Louis Kahn and Robert Venturi. Six features highlighted the work of Davis, Brody & Wisniewksi, including projects such as the Beth Israel Memorial Center in Woodbridge and the Philip Drill House in West Orange.

Photo (right): Exterior of Candy Garden photographed by Alexandre Georges, scanned from Progressive Architecture, July 1956, page 96.

Photo (right): Exterior of Candy Garden photographed by Alexandre Georges, scanned from Progressive Architecture, July 1956, page 96.In the postwar period, New Jersey faced unprecedented growth and development that had serious implications on the built environment. When considering modern architecture, especially in the shadow of New York City, the tall, elegant glass and steel skyscrapers take center stage. However, during the twentieth century, New Jersey's population experienced linear growth, whereas Manhattan's dwindled. New Jersey needed new buildings of all types that would accommodate the influx of people, at all stages of their lives. Though these buildings are much less glamorous than the towers of glass and steel, they are no less important to an understanding of modernist architecture in America.

With this in mind, I organized my architectural findings into five categories:

- Auto Oriented (highways and drive thrus)

- Suburban Expansion (Schools, hospitals, swim clubs, shopping centers)

- Urban Renewal (Redevelopment plans & public housing)

- Public Buildings (Housing for the upper middle class)

- Residences (Universities, civic centers, etc.)

For the purposes of this article, I will focus on the most innovative forms which lie in the first three categories. These buildings, plans and schemes tell the story of the built environment in New Jersey which can be found in communities across the United States. For those that had access to the tremendous economic growth in the postwar period, it is a story of how suburbs grew with access to the automobile and a life of increased opportunities for leisure. For those who were denied access to this growth because of their race, it is a story of how professionals sought to compensate for this inequality through design. The sites in New Jersey highlighted through the pages of Progressive Architecture are pieces of American cultural heritage that showcase important changes at a pivotal moment in architectural history.

1. Auto- Oriented Architecture

Auto-oriented highlights an important aspect of the suburban New Jersey experience, and one which was new to postwar life. The availability of the automobile and its new role as the primary mode of transportation changed the way Americans lived their lives and conceptualized space.

Photo (right): Photo of Toll Collection Facilities, scanned from Progressive Architecture, September 1954, page 98. Photo credit Samuel Gottscho and William Schleisner.

Photo (right): Photo of Toll Collection Facilities, scanned from Progressive Architecture, September 1954, page 98. Photo credit Samuel Gottscho and William Schleisner.The New Jersey Turnpike, featured in the September 1954 issue, is likely the most prominent example of modernism in the state. The architectural scheme included not only the feat of civil engineering through 118 miles of roads, but also a series of tollbooths, maintenance and equipment stations, restaurants and rest stops and uniform signage throughout the highway.

Writing about the Turnpike, the author states:

“The first [expressway] to be completely designed and built for its specific purpose without federal or state aid, the Turnpike has served as a pacesetter for the dozens of self-liquidating, bond-financed toll roads now on the planning boards or under construction throughout the country.”

The Turnpike is at the advent of a new auto-oriented cultural landscape, built to accommodate the leisurely driver along his journey throughout New Jersey. The complex design scheme shows how multiple design and engineering elements coalesce to create a unique experience for the motorist, unlike any other road or highway in the state.

A second auto-oriented architectural artifact was the location of Loft's Candy Garden, located in the median strip of Route 22 in Union, New Jersey. Designed by architect Meyer Katzman in 1956, the location represents Manhattan chain store Loft's first venture into the suburbs. Located in the median, the space was designed with the leisurely motorist in mind. Visitors were encouraged to stop at the location in the median strip, convenient for both north and southbound travelers, and enjoy candy demonstrations and outdoor seating on the terrace. In the twenty first century, with the ubiquity and necessity of the highway, not only have these initial auto-oriented destinations disappeared but their function seems unfathomable.

2. Suburban Expansion

The architecture of suburban expansion features buildings that encompass all aspects of life, including schools, shopping centers, work places, swim clubs, a nuclear energy plant, and two cemeteries. All of these new building types attempted to cope with rapidly expanding suburbs.The Waldwick Elementary School, designed by David Tukey of Gina, Ketchum and Sharp, was featured in the April 1957 issue. In order to preserve the natural features and residential character of the suburban neighborhood, groups of one story classroom buildings were planned that mimicked the housing in the neighborhood. The plan allows for the elementary school to constantly expand. New buildings can be constructed throughout the site's thirteen acres, all the while conforming with its suburban context.

The architecture of suburban expansion features buildings that encompass all aspects of life, including schools, shopping centers, work places, swim clubs, a nuclear energy plant, and two cemeteries. All of these new building types attempted to cope with rapidly expanding suburbs.The Waldwick Elementary School, designed by David Tukey of Gina, Ketchum and Sharp, was featured in the April 1957 issue. In order to preserve the natural features and residential character of the suburban neighborhood, groups of one story classroom buildings were planned that mimicked the housing in the neighborhood. The plan allows for the elementary school to constantly expand. New buildings can be constructed throughout the site's thirteen acres, all the while conforming with its suburban context.Photo (right): Waldwick Elementary School by David Tukey of Ketchum, Gina & Sharp, located in Waldwick, NJ. Likely unbuilt or lost. Scanned from Progressive Architecture, April 1957, page 123.

Replication was important as well to Victor Gruen & Associates' design for the chainstore Penn Fruit, whose Audubon, NJ location was featured in the July 1956 issue. The innovation highlighted in the design was the creation of an iconic gently sloping arch motif to be repeated in the store's future locations. The building provided an answer the design problem of a store to “not only serve its merchandising purpose but also be sufficiently distinctive in form and appearance that it becomes an instantly recognizable trademark.”Though Penn Fruit no longer continues as a supermarket chain, its issues inbranding anticipates the many “big box” retailers lining today's American highways. The ability for buildings to be builtefficiently and easily reproduced are the most important traits that define suburban architecture. Though rapid growth has rendered many 1950s solutions obsolete, these principles are important tenants of modernism. The buildings highlighted in the pages of Progressive Architecture show innovation in the American built environment: a time when the replicability of chain stores represented innovation instead of monotony.

3. Urban Renewal

The final category in my study is the foil to suburban prosperity: architectural solutions to urban decline. Modernist urban renewal is most often featured as a part of the “tower in the park” paradigm. Ivy Hill Apartments in Newark, designed by Kelly & Gruzen and featured in the 1952 issue, represent the modernist's vision for urban living: towers which provide residents with copious outdoor space and the latest amenities of modern living.

The final category in my study is the foil to suburban prosperity: architectural solutions to urban decline. Modernist urban renewal is most often featured as a part of the “tower in the park” paradigm. Ivy Hill Apartments in Newark, designed by Kelly & Gruzen and featured in the 1952 issue, represent the modernist's vision for urban living: towers which provide residents with copious outdoor space and the latest amenities of modern living. Photo (right): The Ivy Hill Apartments, designed by Kelly & Gruzen, received a citation in Progressive Architecture’s 1952 awards for its superior site plan. The apartments were built with Federal Housing Administration financing to attract middle class tenants. Scanned from Progressive Architecture, January 1952, page 64.

One of the important findings of my survey, however, were two redevelopment plans, one in Camden and the other in Trenton, which seem to anticipate New Urbanist design principles. Thomas Vreeland Jr and Oscar Newman's 1963 redevelopment plan for Cooper's Point in Camden called for the renovation of the early twentieth century row housing in the neighborhood, in addition to medium to high rise development on the Delaware waterfront overlooking Philadelphia. Frank Schlesinger, Attilo Bergamasco and Richard Cripps' 1966 plan for the redevelopment of Mercer and Jackson Streets in the Mill Hill neighborhood of Trenton emphasized creating a pedestrian-friendly commercial corridor with mixed use development and making better use of parking lots by building row houses at the neighborhood's scale.

One of the important findings of my survey, however, were two redevelopment plans, one in Camden and the other in Trenton, which seem to anticipate New Urbanist design principles. Thomas Vreeland Jr and Oscar Newman's 1963 redevelopment plan for Cooper's Point in Camden called for the renovation of the early twentieth century row housing in the neighborhood, in addition to medium to high rise development on the Delaware waterfront overlooking Philadelphia. Frank Schlesinger, Attilo Bergamasco and Richard Cripps' 1966 plan for the redevelopment of Mercer and Jackson Streets in the Mill Hill neighborhood of Trenton emphasized creating a pedestrian-friendly commercial corridor with mixed use development and making better use of parking lots by building row houses at the neighborhood's scale.Photo (right): The Cooper’s Point Redevelopment Plan by Thomas R. Vreeland, Jr and Oscar Newman won P/A’s 1963 award for Urban Design. The plan focused on renewing the waterfront, preserving existing housing, developing a commercial corridor, and improving transportation access. Scanned from Progressive Architecture, January 1963, page 99.

Like many master plans, it is hard to see today what has been implemented in these neighborhoods. Due to the continuing struggles of Trenton and Camden, our historical memory sticks to easily recognizable “Tower in the Park” urban interventions when considering modernism's legacy. However, the pages of Progressive Architecture capture how plans and ideas were considered in their time to be innovative, whether built or unbuilt. The plans for the Mercer-Jackson neighborhood in Trenton and Cooper's Point in Camden show that there can be more nuance to the conventional narrative of urban renewal.

Photo (right): Exit 9 Toll Collection Facilities from October 2013, courtesy of Google Street View. While structures appear to be original, details like the lettering no longer remain.

Photo (right): Exit 9 Toll Collection Facilities from October 2013, courtesy of Google Street View. While structures appear to be original, details like the lettering no longer remain.My survey of Progressive Architecture for New Jersey sites revealed several important tensions when considering modern architecture. First, not all modernist architecture held in high regard today was what the design profession considered to be cutting edge at the time it was built. I found many of the forebears to today's most bemoaned buildings, such as chain big box stores and highway rest stops. While today these buildings represent the worst of suburban sprawl, they were once hallmarks of a new era. The second tension I found was because there were many buildings, sites and plans featured in my survey that were never built. Similarly, many buildings, especially those built at the advent of the suburban age, have been completely erased from our landscape. While so much of preservation focuses on saving what remains, we must also find ways to fit these forgotten buildings, whether they have been torn down or have never been built, into our understanding and preservation of modernism.

Photo (right): The Penn Fruit location has changed significantly since 1956. Today, an Acme has retrofitted the distinctive gently sloping arch into a more typical suburban grocery store program. Image joshaustin610 via Flickr.

Photo (right): The Penn Fruit location has changed significantly since 1956. Today, an Acme has retrofitted the distinctive gently sloping arch into a more typical suburban grocery store program. Image joshaustin610 via Flickr.New Jersey is a state whose historical importance is largely tied to its role as “the Crossroads of the American Revolution.” However, the tremendous population growth New Jersey experienced in the postwar period had huge implications for the built environment. The pages of Progressive Architecture tell the story of how our architects and urban planners innovated in terms of these changing circumstances: growing booming suburbs and accommodating shrinking cities. As populations continue to grow and expand, this historical moment will only become more important to understand and to preserve.

Marlana Moore graduated from Rutgers University in 2013 where she studied architectural history, urban planning and preservation. She will begin the Masters of City & Regional Planning program at the Bloustein School of Rutgers in Fall 2014. She recently presented her research for Docomomo US New York/Tristate at the 2014 New Jersey History & Preservation Conference.