By Timothy Rohan

By Timothy Rohan

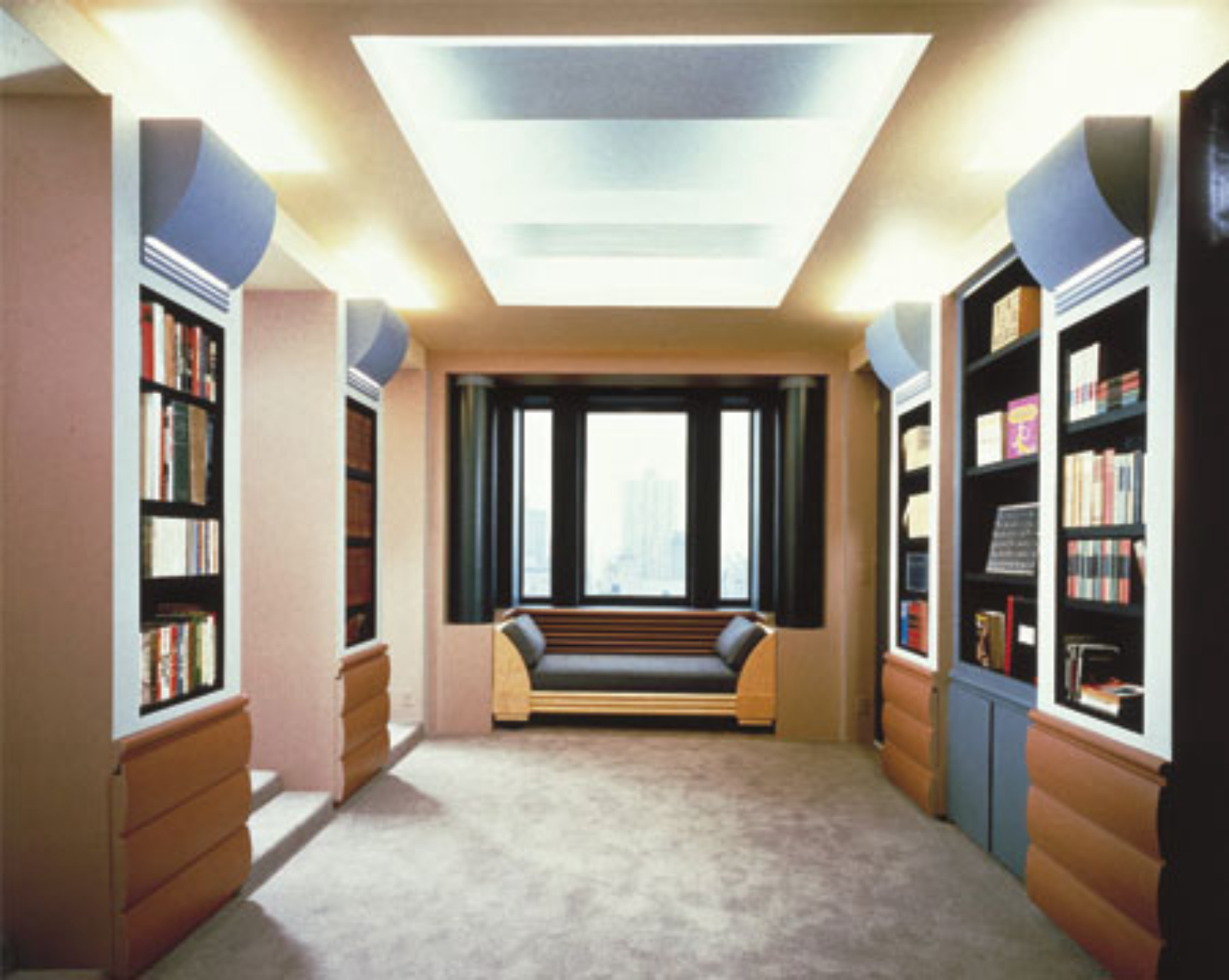

Inside a Brooklyn Museum warehouse is a remarkable relic of postmodernism: a suite of rooms designed and built between 1979 and 1981 by Michael Graves for Susan and John Reinhold’s apartment at 101 Central Park West, New York. This little known artifact has never been publicly displayed since being dismantled and donated to the museum in 1986. Part of a larger duplex, the suite consists of a library and child’s bedroom. Built-in bookshelves, wall paneling, and multi-tiered ceilings define the rooms, forming a completely designed, cohesive interior recalling French boiserie in concept. The suite exemplifies Graves’ signature style of muted colors and abstracted classicism, best known from his landmark Portland Building of 1982.1

All Images: Michael Graves (American, 1934-2015). Library and Child's Bedroom from the Reinhold Apartment at 101 Central Park West, New York, New York, 1979-1981. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of John, Susan, and Berkeley A. Reinhold, 86.179. Creative Commons-BY. Credit: © Peter Aaron/Esto

The Reinhold rooms are important as rare examples of postmodernist interior architecture; as a work by the recently deceased Michael Graves (1934-2015) when he was on the threshold of great fame; and though not installed, as some of the only twentieth-century period rooms in an American museum collection. While many important modernist residential interiors still exist in houses, few modernist apartment interiors survive, and the Reinhold rooms may be the only postmodernist ones. Despite its relatively recent vintage, postmodernist architecture in general is rapidly disappearing.

The Reinhold rooms have an even greater significance as part of a larger, once well-known, but now little remembered body of residential interior work by modernist and postmodernist architects in New York, which is the subject of a new book I am currently researching. Between 1965 and 1985, New York architects explored innovative aesthetic, spatial, and social dimensions for living when they renovated Manhattan apartments, townhouses, and lofts. These architects ranged from the famous, to those on the rise, and to those once well known but now largely forgotten. They included Paul Rudolph, Robert A.M. Stern, Charles Gwathmey, and Alan Buchsbaum, to name to just a few. Seizing the interior from interior designers, they saw it as a realm for experimentation, a way to expand or establish their reputations, and eventually as an important source of income in the deepening recession of the 1970s. Widely publicized at the time, the resulting new “interior architecture” expanded upon modernism’s earlier interior investigations and led in fresh directions. In Manhattan, international design tendencies were synthesized amidst urban decay, with the city thriving artistically even as social disorder and financial crises brought it close to collapse.

The Reinhold Apartment was one of the most fascinating examples of this phenomenon because several important architects of the era worked on it successively. 101 Central Park West was a white glove, Renaissance Revival apartment building completed by Schwartz and Gross in 1930. It had cavernous apartments of the kind which were often divided in the mid-twentieth century and then recombined in the late 60s and 70s as the West Side rebounded. In 1971, Robert A. M. Stern and John Hagmann redesigned an upper floor duplex at 101 which later became the Reinhold Apartment. Stern himself lived in the building. Removing many traditional decorative elements, walls, and ceilings to make more open flowing spaces, the architects conceived an all-white interior which epitomized high modernism and was inspired by Le Corbusier’s work of the 1920s. This scheme typified Stern’s work before he adopted the more historically inspired vocabulary for which he is best known today. The architects intervened in bold ways at 101. Stern and Hagmann carved a double-height living room out of the apartment’s center topped by a master bedroom loft. They modeled the room upon downtown artists’ lofts and similar rooms by Paul Rudolph, who had taught Stern at Yale.

The apartment demonstrated that a surprising amount of design freedom was possible within a confined space. Articulating the appeal that interiors held for him and his contemporaries, Stern said in an article about the 101 renovation, “Buy a city apartment and you are probably buying a box. But you can make a totally personal world inside that space. The only place this world has to touch what's really outside is at windows, doors, places where structural elements have to stay where they are.”2Speaking in 1972, Stern’s words have a social and architectural relevance, anticipating the marked interiority of the “me decade,” the 1970s. This interiority is also a characteristic of postmodernism, which hit its full stride late in that decade. Michael Graves stepped in to the evolving environment of the 101 apartment at exactly that moment.

Views of In Situ Bedroom |  |

After acquiring the duplex in the late 1970s Susan and John Reinhold asked Graves, postmodernism’s rising star, to help improve it. The Reinholds were members of the New York art world. Susan dealt in early twentieth century posters and graphic design. John was a diamond dealer and close friend of Andy Warhol, who wryly commented in his diaries about how it took Graves two years to complete the commission.3It should not have taken that long. Leaving the Stern and Hagmann renovation intact elsewhere, the Reinholds asked Graves to transform a guest suite into a library for Susan’s books and an adjoining bedroom and playroom for their young daughter, Berkeley.

Exemplifying the increasingly historicist direction of postmodernism, Graves conceived of the library as a basilica with two side aisles formed by piers containing bookcases. Though the renovation was ultimately expensive, the interiors were made from low-cost plywood and sheetrock. Using inexpensive materials even for well-off clients was characteristic of the period’s interior experimentation. These materials have proven difficult to preserve. The piers resembled abstracted pilasters whose capitals were semicircular wall sconces. They cast compelling shadows across a tiered ceiling above. A reply to the still extant modernist whiteness elsewhere in the apartment, Graves’ complex color scheme of blues, browns, and yellows further defined and enriched the suite’s spaces. This color palette was among Graves’ most often emulated contributions to postmodernism. Graves referenced himself in the library, marking one end of the room where an altar might have been in a basilica with a mural of his own design, a Le Corbusian-style still life. He also installed a cubist-inspired relief by himself in a corridor niche.

Berkeley Reinhold’s adjoining bedroom was unlike those of most young girls. No pink canopy bed for her! Graves executed it in the same somber manner as the library. Demonstrating their sophistication, the Reinholds adorned the room with a portrait of Berkeley by another of the era’s rising stars, Robert Mapplethorpe. The precocious Berkeley published an article about its charms and flaws in 1981. A discerning critic, she said it was “the best room in the whole house,” but the shelves were too narrow for her books and records.4A poster child for postmodernism in itself, Grave’s suite for the Reinholds was published several times after its completion. In 1990, it appeared as an illustration in an article by Paul Goldberger in The New York Times about how the traditional room had nearly superseded the open plan in recent years.5

However by 1990, the Reinhold suite was no longer intact. It was inhabited briefly, like so many of the remarkable architect-designed Manhattan residential interiors of the late twentieth century, most of which have not survived. The city’s creative destruction is relentless. Architectural experimentation made possible by affordable real estate became less feasible after New York’s economic recovery of the 1990s. Once the Reinholds divorced in the mid-1980s, the apartment was sold and rebuilt by Diana Agrest and Mario Gandelsonas in 1989 using more durable, expensive materials in a manner recalling the work of Adolf Loos. Recognizing the Graves suite’s uniqueness, the Reinholds donated it to the Brooklyn Museum in 1986. The Museum hoped that the suite would join its impressive collection of period rooms as a characteristic if rare example of postmodernism. This has not happened yet. The period room is as out of fashion today as postmodernism. Perhaps one day the Reinhold suite will emerge from storage to take center stage as either the centerpiece of a Graves retrospective, an exhibition about postmodernism, or a much needed show about Manhattan’s lost but remarkable modernist domestic interiors.

Views of In Situ Playroom |  |

Timothy M. Rohan teaches architectural history at UMass Amherst. He is the author of The Architecture of Paul Rudolph (Yale University Press, 2014). He is currently a fellow at the Newhouse Center for the Humanities at Wellesley College where he is working on a new book about modern and postmodernist residential interiors in Manhattan.

Notes

1. My thanks to Barry R. Harwood and Alison Karasyk for making files about the Reinhold Rooms available to me at the Brooklyn Museum in March 2015.

2. Melissa Sutphen, “Remodeling within the Box,” House Beautiful, May 1972, p. 115.

3. Andy Warhol, The Andy Warhol Diaries, edited by Pat Hackett (New York: Warner books, 1989) p. 566-67.

4. Berkeley Reinhold, “MY Apartment,” Express, Vol. 1, no, 1, Fall 1981, p. 15.

5. Paul Goldberger, “Four Walls and a Door,” The New York Times Magazine, Home Design, Part 2, October 14, 1990, p. 40, 66.