Editorial Introduction

Erich Mendelsohn’s Park Synagogue building in Cleveland Heights is one of the most influential Modernist sacred spaces of the postwar era, and certainly one of the most influential synagogues in the United States. Completed between 1950 and 1953, Park Synagogue is both prototypical and outstanding. The bucolic setting, surface parking lot, flexible partitions to accommodate the flood of High Holiday worshippers, expansive education wing: each was a major trend in postwar synagogue design and a response to the suburbanization of American Jews. But whereas other designers may have struggled to avoid explicit historicist references in their attempt to accommodate a new kind of Jewish space, Park Synagogue, and especially the sanctuary’s monumental, Expressionist dome, succeeded in harkening back to Old World traditions. Mendelsohn achieved a Modernism that never broke away from the past.

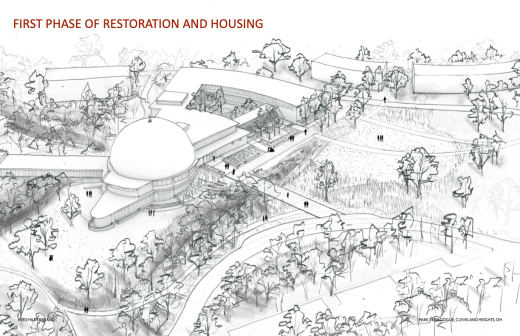

A case study for other postwar synagogue designers, Park Synagogue is now becoming an important precedent in the preservation and adaptive reuse of Modernist sacred places. In 2005, after a half-century of use, the congregation moved five miles down the road to a new campus, Park Synagogue East. In 2021, the congregation sold the original 28-acre Cleveland Heights campus to Sustainable Community Associates (SCA), a local real estate development firm. SCA’s proposal for a multi-phase redevelopment project entitled Park Arts centers on an arts and culture hub, much like the adaptive reuse of Mendelsohn’s B’nai Amoona synagogue outside of St. Louis (now the Center of Creative Arts) and Temple Tifereth-Israel in Downtown Cleveland (now the Milton and Tamar Maltz Performing Arts Center for Case Western Reserve University). SCA formed Friends of Mendelsohn, a nonprofit, to own the original Mendelsohn buildings and steward the non-profit components of the larger redevelopment. Recently, SCA announced that Oberlin College and Conservatory’s new BFA in Integrated Arts will become the project’s anchor tenant. New housing is set for the perimeter of the site.

To learn more about the process of transforming Park Synagogue into Park Arts, Gianfranco Grande and Kevin Block of Partners for Sacred Places first spoke with Eric Zamft and later Naomi Sabel. Zamft is the Director of Planning, Neighborhoods, and Development for the City of Cleveland Heights. Sabel, along with Josh Rosen and Ben Ezinga, is one of the founders and principals of SCA. Sabel, Rosen, and Ezinga are now following the lead of a mentor and fellow Oberlin graduate, Richard Baron, who redeveloped the Center of Creative Arts. Together, Zamft and Sabel describe the collective effort and cooperation necessary for this exciting project to move forward. As they reiterate in their comments below, many different groups have made vital contributions to the project in addition to the intrepid developers, including municipal staff and the mayor’s office, Ohio SHPO staff, other state officials, and local advocacy and neighborhood groups. Because of this collective reinvestment in one of our country’s most remarkable examples of Modernist religious architecture, the original Park Synagogue campus will remain a vital community asset in Cleveland Heights. It will also remain a sacred place. At least for the next 99 years, the congregation will be able to host High Holiday services, as well as other kinds of performances and gatherings, under the canopy of Mendelsohn’s great dome.