Reader note: The following article is adapted from Lizabeth Cohen's Keynote Address "Revitalizing the Post-Covid City: What We Can Learn from the Past," presented at Preserving the Recent Past 4, on March 20, 2025, in Boston.

Good morning. We are gathered here over the next two days to discuss strategies for preserving and conserving modern architecture and design in the United States, specifically the built environment that has emerged since the Second World War. Although this era may barely seem like history in an American city as old as Boston, where we now sit, we are in fact talking about the architectural production of eight decades.

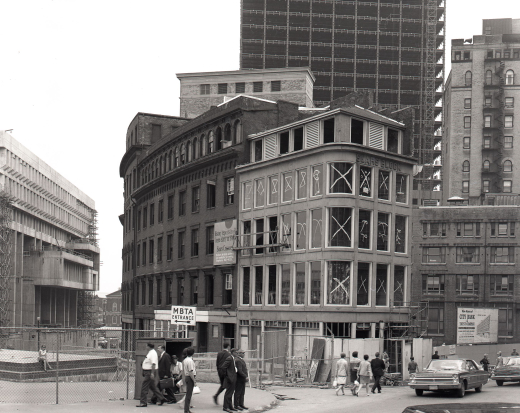

Not surprisingly, much of our discussion at this conference will focus on particular buildings and sites and the architects who designed them, as we share approaches to saving representative fragments of the fast-disappearing modernist legacy of the postwar U.S.

But one building’s preservation is not so easily isolated. No building stands alone in space or even in time. Inevitably, it is part of multiple contexts that we need to be mindful of and seek to remember as well. I am an historian by discipline, not an architect, architectural historian, or preservationist. My focus has been on the history of the United States in the 20th century, with particular attention to cities in the postwar era. And as an historian, I see my job as putting people, places, and events in context to better interpret their meaning and significance.

Therefore, I will set out today to move us beyond the singular architectural specimen to illuminate several contexts that I think are crucial to consider – and memorialize – in preserving postwar modern architecture and landscapes. And I hope that we can carry awareness of the importance of these contexts into the panel discussions that will follow at the conference. I am pleased to see that quite a number of sessions will, in fact, explore these issues. My contexts for today include that of history, of surroundings, and of use; in other words, contexts of time, of space, and of utility. Let’s begin with History.

The Context of Time

Historic preservation has had many successes since its embedding in the legal code in the mid-1960s, but it still struggles with the societal tension between protecting the material achievements of the past and welcoming new creations in the present and future that convey continued economic and cultural vitality.

The post-WWII historic preservation movement, in fact, was born out of this tension. After the war ended, American cities were stagnant. During the previous decade and a half of the Great Depression followed by austerity on the homefront, most cities saw the erection of very few new buildings. Residential projects, as well as business investments downtown, were put on hold. Consequently, as the postwar era dawned, a huge housing crisis unfolded, as soldiers returned from war and long-delayed marriages and births put even more pressure on an inadequate and deteriorating housing stock.

Moreover, as Black Southerners moved north with the Second Great Migration in search of good industrial jobs and other opportunities, housing became even tighter – and more racially segregated.

Although there were a number of possible solutions, the one that the nation embraced was to grow the suburbs by cutting highways through what had been farms and forests to improve access to urban hinterlands.