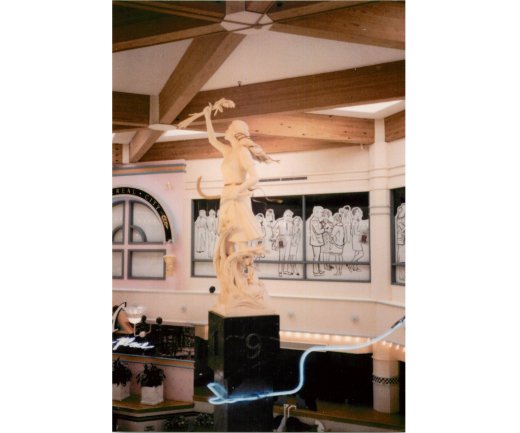

Was it to be a missing person’s report, or more of a personal ad?

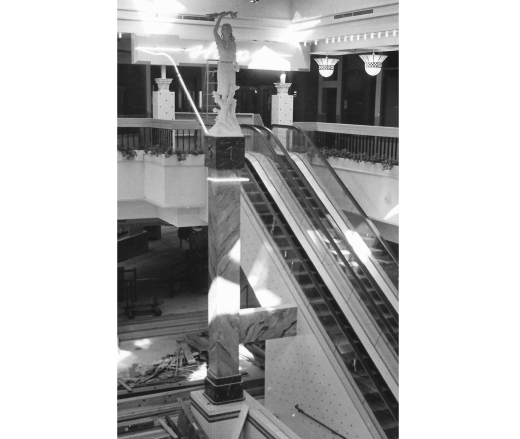

Middle-aged female architect ISO a goddess she recollects from her youth

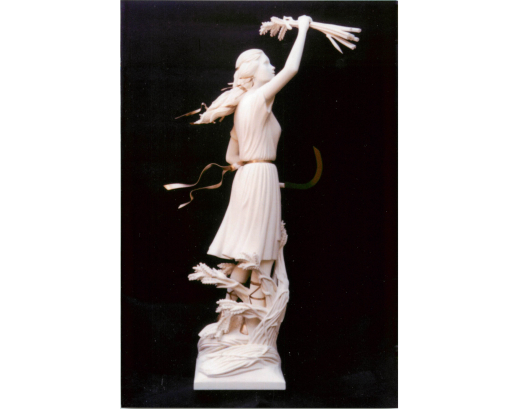

About seven feet tall; long, flowing locks; triumphant pose

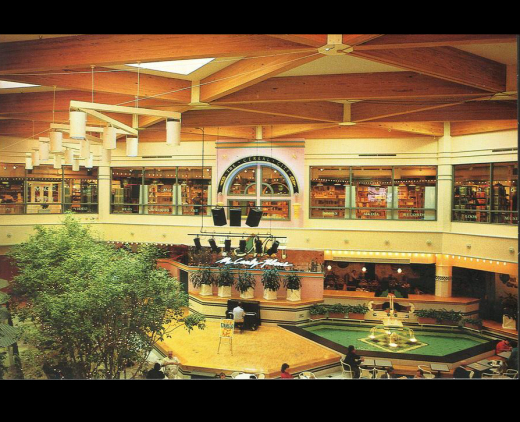

Last seen: Battle Creek, Michigan, sometime in the late 1980s, in the food-court of a mall

I see now that it’s starting to read a bit like an episode of Stranger Things, but pour yourself a bowl of corn flakes and settle in.

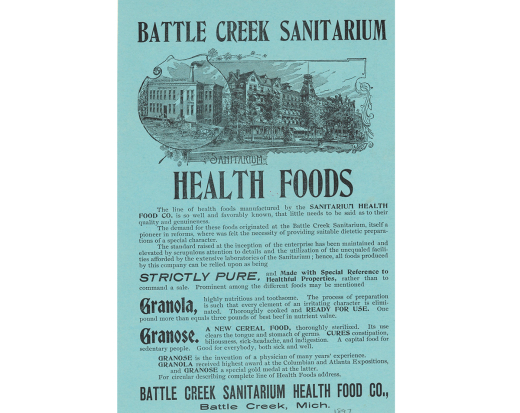

Battle Creek, Michigan: a mid-sized midwestern town that grew up around the breakfast cereal industry. It has been home to Ralston and Post cereal factories, and Kellogg, the patron manufacturer of the town. Breakfast cereal saturates the built and sensory environment of Battle Creek–not only from the factories that encircle the town and fill the air with a burnt-sugary smell–but in the city center as well.

The town’s largest building, a 14-story behemoth, looms on the edge of the commercial district. Constructed as a health resort by the eccentric J.H. Kellogg in the late 1860s, the “sanitarium” (as it was christened) attracted followers of Seventh-Day Adventist principles with a program of flaked cereal breakfasts and wholesome exercise. It was the happening place in its day, with visitors including Amelia Earhart, Sojourner Truth, Henry Ford, John D. Rockefeller Jr, and Thomas Edison.[1]