Primary classification

Designations

None. But due to the transfer of air rights from the landmarked 55 Wall Street, 60 Wall Street must maintain a harmonious relationship to the landmark. This section of the NYC code requires the Landmarks Preservation Commission review of changes to that exterior relationship.

Author(s)

How to Visit

Atrium is open to the public. Direct access via the 2, 3 trains at Wall Street.

Location

60 Wall StNew York, NY, 10005

Case Study House No. 21

Lorem ipsum dolor

Other designers

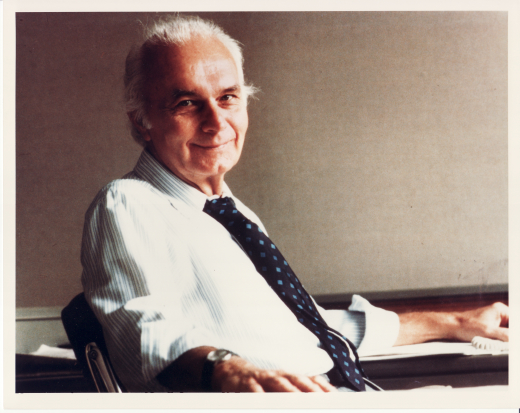

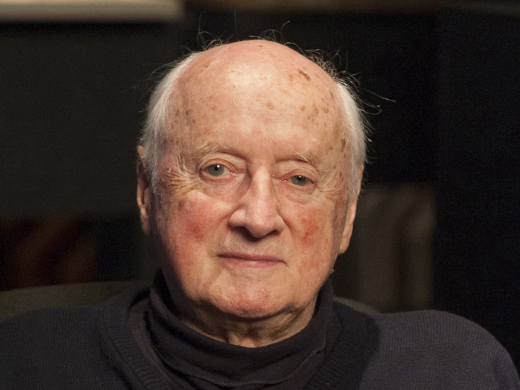

Architect: Kevin Roche, John Dinkeloo; Project Manager: James Owens; Structural Engineer: WSP Cantor Seinuk; General Contractor: Tishman Realty & Construction; Steel Contractor: Frankel Steel