Awards

Advocacy

Award of Excellence

Commercial

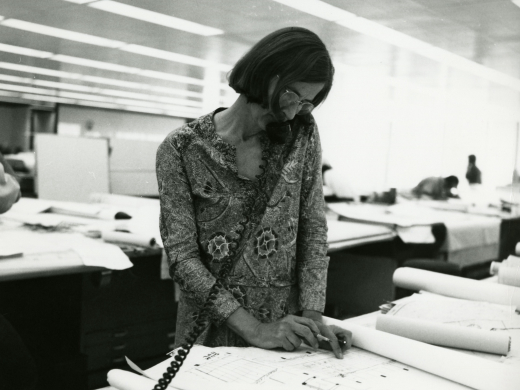

An Advocacy Award of Excellence is given to the Cincinnati Preservation Association and the coalition of local advocates, including City Councilmember David Mann, for their efforts to save Cincinnati’s Terrace Plaza Hotel. Designed by Natalie de Blois of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), the Terrace Plaza Hotel opened in 1948 as the country’s first International-style hotel. In addition to the hotel, the building included retail space and a high-end restaurant with a mural by artist Joan Miró. The business began to struggle in the late 1970s but managed to hang on until it closed for good in 2008. It has sat vacant since then, changing owners and experiencing demolition by neglect. The Cincinnati Preservation Association led the effort to preserve the building through educational efforts, statewide and local designation, and creative means to find a sympathetic developer. Terrace Plaza is not “out of the woods” yet, but thanks to the work of the Cincinnati Preservation Association, other local advocates, and the support of councilmembers such as David Mann, the tide is turning in the right direction.

“The coalition deserves praise for being extremely proactive, reaching out to a broad community of stakeholders and elected officials to awaken their city to Terrace Plaza's high level of significance.”

-Liz Waytkus, Docomomo US Executive Director

"At the time, SOM was cutting edge for employing female architects in their firm, but for so many years only the male figures were recognized. It’s nice to see women architects and designers such as Natalie de Blois coming out of the shadows and getting the recognition they deserve.”

Primary classification

Designations

Added to the National Register of Historic Places, August 21, 2017

Author(s)

How to Visit

Currently closed.

Location

Terrace Plaza Hotel

15 West 6th StreetCincinnati, OH

Country

Hamilton

Case Study House No. 21

Lorem ipsum dolor

Designer(s)

Natalie de Blois

Architect

Nationality

American

Morris Lapidus

Architect

Nationality

American, born in Russia

Skidmore Owings & Merrill (SOM)

Other designers

Morris Lapidus, Vincent Kling