Primary classification

Terms of protection

Designations

Author(s)

How to Visit

Daily public tours (Seasonal)

Explore Modern House Partnership

Your Docomomo US membership card will grant you a 20% discount off tour tickets using code DOCOMOMO.

More sites in the Explore Modern Partnership

Location

798-856 Ponus RidgeNew Canaan, CT, 06840

Country

US

Case Study House No. 21

Lorem ipsum dolor

Designer(s)

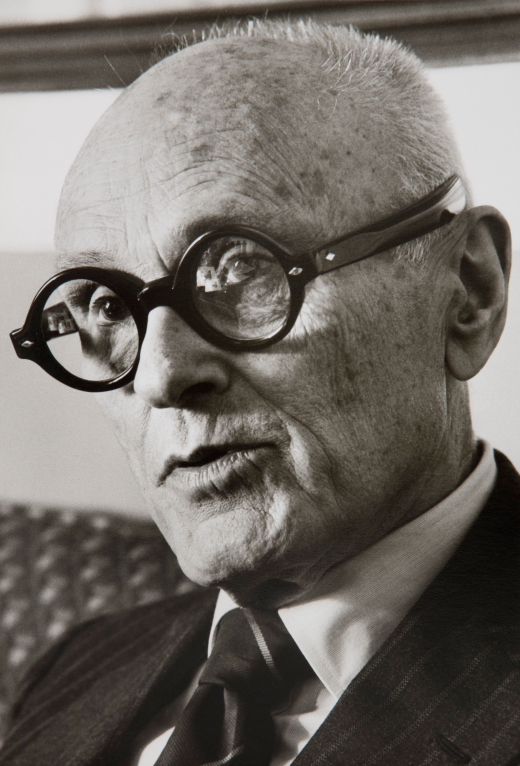

Philip Johnson

Architect

Nationality

American

Other designers

Architect: Philip C. Johnson

Landscape/garden designer: Philip C. Johnson

Other designer: John Burgee

Consulting engineers: steel subcontractor, Fred Horowitz, Gotham Construction, Port Chester, NY

Building contractors: John C. Smith, Inc., New Canaan, CT.. Louis E. Lee Co., New Canaan, Ct.; E.W. Howell Co.